We were victims of our own success. Because we were able to generate the printing/publishing map of a text using the British Short Title Catalogue with only moderate pain and a few tears, we were all tasked with generating a map via scraping information from the Dissenting Academies Online website.

Upon beginning this task, I took a deep breath and whispered to myself, “This won’t hurt that much”. Boy, was I wrong. When deciding on query to ask of the Dissenting Academies Online website, I settled for the library records spanning from 1843-1844. There were over 1,000 results from this search. To keep myself from going mad, I used the first 17 sheets of results. I know this is only a minor dent in ALL of the data. However, from what I used one can still see a few interesting trends, such as the same person repeatedly checking out the same book. As mentioned in class, this possibly happened because many of the academies would not allow their books to physically leave the library.

The art of scraping a website, while not my strong suite, was not terrible. I was pleasantly surprised. However, while it was all outlined for us in elaborate walkthroughs, manipulating the data in Google Sheets proved to be an expletive inducing experience. There was a “son of a b*@%#” here, and a “f!&*” there; nothing too out of the normal.

Once I “tamed” the data (or thought I had); it was time to wrestle with Kumu. In one corner, there was me: an already battle-worn SLOB warrior (who was still having flashbacks about last weeks “bloodshed”). Then in the other corner was Kumu: a new, fresh-faced opponent, whose methods and tactics in the ring were still unknown to me. Unfortunately, to be very anticlimactic, Kumu was fairly simple to use. The only frustrating part was figuring out what was up with three sections of my Google Sheets data. While I never exactly figured out what was wrong with the data, I was still able to generate a map. Is the map beautiful? No. Does the map make much sense? Not really. However, what I did get out of this is potentially a new skill that I not only can apply for later in this class with our final project, but, it also has the potential to be used in other areas of my academic life.

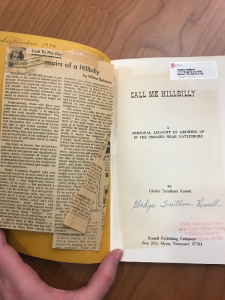

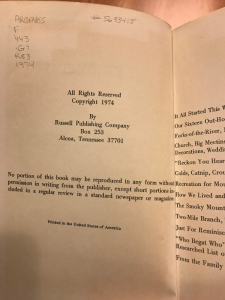

We were also interested in taking a look at books that were well worn and had obvious use. They pointed us in the direction of the collection Gladys Stallard. Gladys was a local woman from Dorchester, which is a specific section of Norton, Virginia, and she had left her book collection to the college upon her death. The particular book I looked at from her collection was “Call Me Hillbilly” by Gladys Trentham Russell; she had written on the inside cover of the book that she acquired it in September 1974. This book talks about the lives of people that grew up in the Great Smoky Mountains near Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Within the book, it features pictures of people from the region and provides their names; alongside this information, Gladys Stallard had written in many birth dates and death dates of the individuals. Mrs. Stallard had also obtained book reviews of the text, and stapled them to the inside of the front cover.

We were also interested in taking a look at books that were well worn and had obvious use. They pointed us in the direction of the collection Gladys Stallard. Gladys was a local woman from Dorchester, which is a specific section of Norton, Virginia, and she had left her book collection to the college upon her death. The particular book I looked at from her collection was “Call Me Hillbilly” by Gladys Trentham Russell; she had written on the inside cover of the book that she acquired it in September 1974. This book talks about the lives of people that grew up in the Great Smoky Mountains near Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Within the book, it features pictures of people from the region and provides their names; alongside this information, Gladys Stallard had written in many birth dates and death dates of the individuals. Mrs. Stallard had also obtained book reviews of the text, and stapled them to the inside of the front cover.  This was interesting, as it made me wonder if perhaps she had personally known the author or had some connection to her. It was easy to tell from the condition and the comments in the book, that this was one that she frequented often.

This was interesting, as it made me wonder if perhaps she had personally known the author or had some connection to her. It was easy to tell from the condition and the comments in the book, that this was one that she frequented often.  Looking at the other books in her collection, it would be safe to assume that Gladys was proud of and interested in preserving the lives and history of the people that live in the South-West Virginia and East Tennessee region.

Looking at the other books in her collection, it would be safe to assume that Gladys was proud of and interested in preserving the lives and history of the people that live in the South-West Virginia and East Tennessee region.