I was pretty close to picking the same book to describe as I did for my first post (since it does, after all, have a few interesting notations at the beginning and end from previous owners), but I ended up selecting another one because I was set on finding one in the original binding. I […]

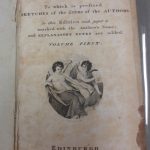

I was pretty close to picking the same book to describe as I did for my first post (since it does, after all, have a few interesting notations at the beginning and end from previous owners), but I ended up selecting another one because I was set on finding one in the original binding. I ended up choosing a book written in 1766 by multiple authors: The Spectator, in eight volumes (see Image 3 in the gallery), which is a series of essays written by Sir Richard Steele, Joseph Addison (Esq.), Eustace Budgell, Mr. Tickell, Mr. Hughes, Dr. Parnell, Alexander Pope (Esq.), Laurence Eusden, Richard Ince, Henry Martyn, John Byrom, Gilbert Budgell, Rev. Richard Parker, Mr. Henley, and Henry Grove. So, basically, a bunch of random names.

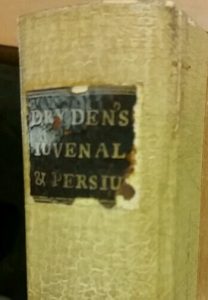

The outside of the book is fairly nondescript save for the spine (see Images 1 and 2 in the gallery). It’s clear where metal tools were taken to the leather; not only are they accented with gold leaf (and red leather dye around the title, as you can see in the gallery) but I could feel the indentations when I ran my finger over them. The actual front and rear of the book feature no distinguishing mark other than redrot (and, to be fair, so does the spine). The endband at the top of the spine has half-broken free of the book, enough so I can see the stitches around it.

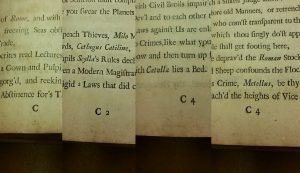

With Dakota’s help, because I have problems with processing and conceptualization, we figured out that the book was probably in duodecimo format (12°) by looking at the chart on page 85 of the Gaskell reading. I noticed that the book is printed on laid paper and has very visible horizontal chain lines, and the length of the cut pages is about 17-17.5 cm (roughly 18~cm uncut estimate). The signatures (which go from A-A3 with three blanks, B-B3 with three blanks, etc, all the way until Ee – but skipping J, V, and W) reveal that this particular book has six leaves to a gathering, leading us to the conclusion that the book is likely in duodecimo format. I’m not excellent at math (like, at all), but I think that at 12 leaves/24 pages a sheet of paper, this book probably took 15ish sheets of paper to manufacture.

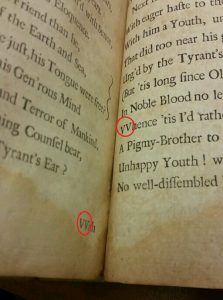

Speaking of the signatures, that’s pretty much the only notable thing there is on the direction line. There are no catch words. However, on the first page of every gathering (A, B, C, D, etc.), there’s a small cross symbol to the right of the signature (see Image 4 in the gallery). I assume this means that all of the pages came from the same press, since the symbol is consistent throughout.

There are only a couple watermarks. On the first blank page I found one reading “1794” (see Image 5 in the gallery – the watermark is faint, but for reference it’s alongside the shadow of my finger). I couldn’t find another watermark on any of the interior pages (probably due to the fact that it’s duodecimo – if I’m right – which means any watermarks probably got cut off) but I did find one on the rear board (see Image 6). If it’s too faint to tell in the picture, it’s a segment of a fleur-de-lis.

There were also a few scribbles here and there, the most notable of which possibly being an owner (see Image 4 in the gallery). I can make out the date as June 25, 1796, and the name seems close to John Whits Smith, but I can’t really distinguish it so your guess is better than mine. There’s also a few pencil marks on a blank page prior to the title page (not pictured because they were too faint in the image) but they indicate that the book was at some point purchased for 3.50 (currency not known).

As for binding, the cover is coming apart slightly, so I could see six places where the paper was sewn to the boards with what appears to be twine, but it’s not much. I couldn’t find anything indicating its state of binding had changed, so I assume I handled it with the same binding in which it had been published.

Finally, cancellations. I have no idea if these count, but I noticed that two pages had been torn out – one right before the title page, and one before the final blank page. They’re right on that teetering point where I’m not sure if they had anything on them to begin with, so I hesitate to call these actual cancellations; I’m guessing someone just needed a piece of paper in a pinch, and decided to utilize some of the blank ones. I did notice that this book had fewer blank pages than some of the other old ones I’ve looked at lately.

If all else fails, I can always blame John Whits Smith-what’s-his-face for those missing pages. I wonder what they were used for.