It’s week two of our SLOB class, and another trip to the archives was called for. This time, we were on a mission; having covered a brief introduction to bibliography, everyone in the class was asked to identify certain traits of a book’s beginnings and figure out the format in which it was made. With […]

It’s week two of our SLOB class, and another trip to the archives was called for. This time, we were on a mission; having covered a brief introduction to bibliography, everyone in the class was asked to identify certain traits of a book’s beginnings and figure out the format in which it was made. With that goal in mind, my partner Mary Haynes and I each grabbed a book and went to work.

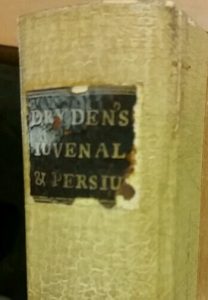

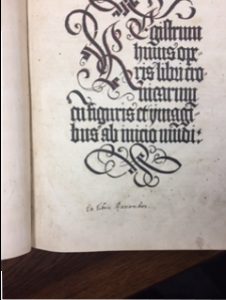

I decided to use the oldest book in the Montevallo archives, which we identified last week: The Satires of Decimus Junius Juvenalis, 3rd ed. with sculptures. Published 1702.

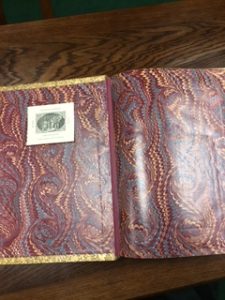

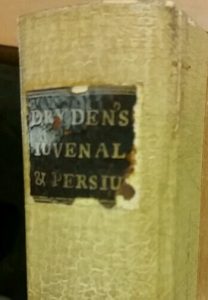

Binding

This book was rebound by C.F. Rothweiler Bookbinding in Zion, Illinois, but the original binding can be seen attached to the new binding. Also, when rebound they cut out the title from the original binding and glued it onto the new spine.

Original Title Binding

Because they simply covered the old binding, there was no effect on the page margins. Although it is unfortunate that the original binding fell apart, because it happened I was able to clearly see the 5 stitch bindings. Another interesting thing about the binding was how it was falling apart. Upon further inspection is appeared to have split in three even sections, but there was evidence of smaller spitting happening as well. Mary Haynes and I came to the conclusion that this book was probably bound in smaller sections that were put into three bigger sections, and then finally bound together as a whole.

Original and New Binding

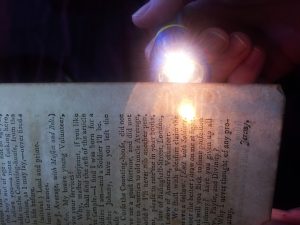

Paper

Right off the bat knew that the paper is laid, not wove. We can tell because of the visible chainlines, mostly horizontal but on pages with images the vertical wires can be seen as well. All of the pages are opened and are trimmed. I could not find a watermark despite looking for quite a while.

Horizontal Chainlines

Vertical Chainlines

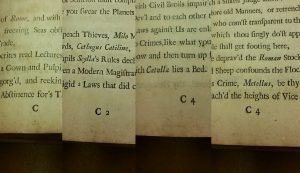

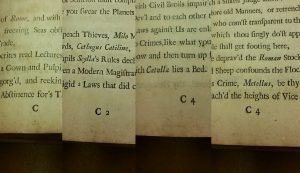

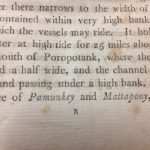

Signatures?

This is where, in my opinion, things got interesting. There were signatures at the bottom of the pages in groups of four. They were denoted by letters of the alphabet, starting with A, and continued until they had to start over with Aa. The interesting part about it was that the signatures were four on, four off. As you can see in the pictures, the pages followed an A1, A2, A3, A4 pattern but then followed by 4 pages without a signature.

Example of Signature

Format

Based on the evidence we found (and a little origami on my part), I’ve come to the conclusion that this book was created using an octavo format. The biggest indicator of this was the signatures and their sets of four. Assuming they used them as a way to make sure the pages were in order when folding, it is safe to also assume that each new set of signatures means a new set of pages. If this is the case, that means there would be 8 leaves and 16 pages, hence, octavo.

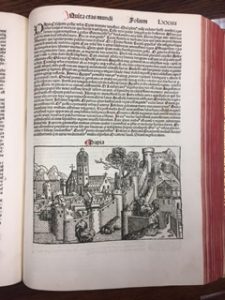

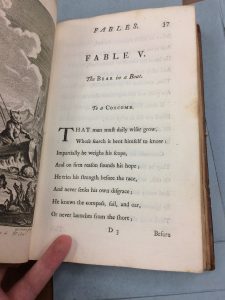

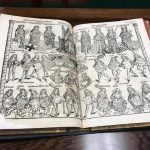

Illustrations?

There were full page illustrations, generally with a black page on the opposing side. Because of that, I assume that the illustrations were printed separately and then bound together with the rest of the pages, but I did not see any glaring evidence of that so I may be wrong. Unfortunately, it slipped my mind to snap a picture of a whole illustration, but in this picture you can see part of one next to title page.

Illustration on Right

Extras

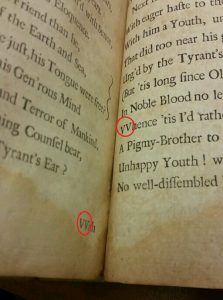

What caught my attention the most from examining the book was the way the typesetting worked. The first thing I noticed was actually a misprint in one of the signature series, as you can see in the pictures below.

Misprint Signatures

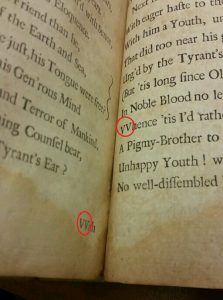

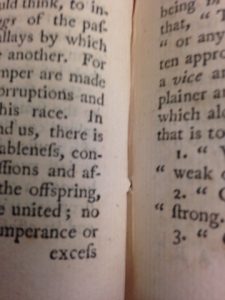

After that I started looking for mistakes, but then stumbled upon something much more telling of the handmade nature of the book. Apparently when a page used too much of a single letter and the printer would run out, they would substitute other letters to make it work, usually with W’s and V’s as you can also see in the pictures.

Ran Out of W’s

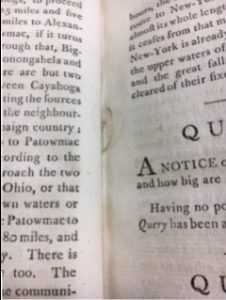

Out of everything I found, I think my favorite was something that apparently was a product of the time this book was written. You see, Mary Haynes and I kept finding all of these works with seemingly random f’s where one would assume s’s would go. Having no idea what this could mean, we asked the archivist and discovered that back then, the f indicated a long s as opposed to a short s sound.

F is Now S

Overall, this visit was super cool and involved a lot of discovery. I had no idea that the structure of a book could be so fascinating, and I have a feeling I will never look at book bindings the same again. (Nor will my friends, because I’m a sharer when it comes to things like this.)

Unfortunately because this book was donated by a prominent woman at our college, librarians pasted a donation label inside the cover. Although it was a good thought to know where it came from, in a way it detracts from the nature of the book. However, it does tell us a good bit about the life of this book. We know it came from the Mabel Gardiners collection.

Unfortunately because this book was donated by a prominent woman at our college, librarians pasted a donation label inside the cover. Although it was a good thought to know where it came from, in a way it detracts from the nature of the book. However, it does tell us a good bit about the life of this book. We know it came from the Mabel Gardiners collection.

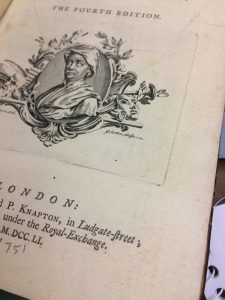

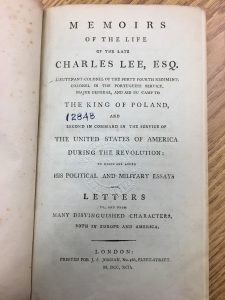

For this assignment I decided return to the book from the first assignment, “Memoirs of the Life of the Late Charles Lee, Esq.,” which was published in 1792.

For this assignment I decided return to the book from the first assignment, “Memoirs of the Life of the Late Charles Lee, Esq.,” which was published in 1792.

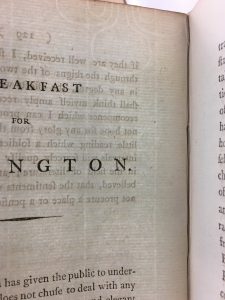

When I started to look at the signatures, I began making notes of everything hoping that what I was looking at would eventually make sense. I also noticed that this book has catchwords. The preface, which was only two pages long, had the signatures b and b2, and the first page of text was marked with a B. The following pages had signatures up to B4, four pages without a signature, and then a page with C for the signature, and this pattern continued throughout the book. This told me that there were 8 leaves per gathering, which made me feel pretty good about having an octavo book in my hands.

When I started to look at the signatures, I began making notes of everything hoping that what I was looking at would eventually make sense. I also noticed that this book has catchwords. The preface, which was only two pages long, had the signatures b and b2, and the first page of text was marked with a B. The following pages had signatures up to B4, four pages without a signature, and then a page with C for the signature, and this pattern continued throughout the book. This told me that there were 8 leaves per gathering, which made me feel pretty good about having an octavo book in my hands.

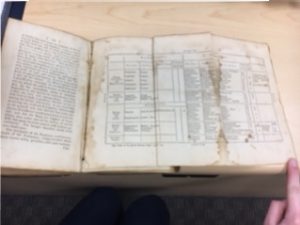

Chain lines! This means that these pages are crafted out of laid paper. The lines run horizontally, and to me, they are beautiful. I am free to make my way through all of the pages of the book; no folds had remained unopened. To my dismay, I did not observe any illustrations whatsoever in this work, and I unfortunately did not witness any water marks either. I am able to note however, that the pages of the book had been trimmed, and at one time would stack nice and neatly on top of one another.

Chain lines! This means that these pages are crafted out of laid paper. The lines run horizontally, and to me, they are beautiful. I am free to make my way through all of the pages of the book; no folds had remained unopened. To my dismay, I did not observe any illustrations whatsoever in this work, and I unfortunately did not witness any water marks either. I am able to note however, that the pages of the book had been trimmed, and at one time would stack nice and neatly on top of one another.

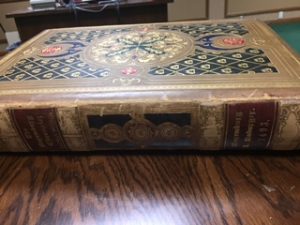

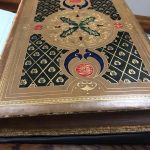

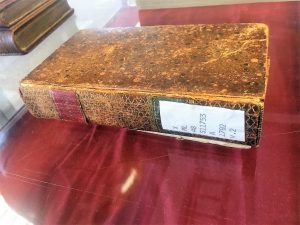

This book has a beautiful brown and black speckled cover, with a small leather strip on the spine imprinted with the gold-filled word “Farces.” The library’s digital catalog titled this as A collection of the most esteemed farces and entertainments, performed on the British stage. I know this because I could hardly make out the title on the spine itself, and when I went to look for a title page, I was abruptly met with the first page of a short play, and consequently turned to the internet to provide me with the title of the book as a whole. I also noticed that there was no publication or printer information within the book itself either. What kind of book, even a book of plays, wouldn’t have this kind of information? Isn’t that what makes a publication? Also, when I began to examine the paper from each play, I noticed that each one had a different type of paper: some laid paper with horizontal chain lines while others woven paper with outer-edge watermarks. Even the text font wasn’t uniform between plays, although size looked pretty consistent.

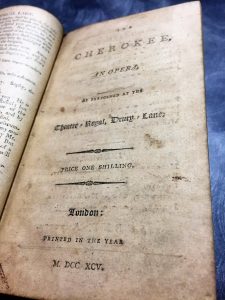

This book has a beautiful brown and black speckled cover, with a small leather strip on the spine imprinted with the gold-filled word “Farces.” The library’s digital catalog titled this as A collection of the most esteemed farces and entertainments, performed on the British stage. I know this because I could hardly make out the title on the spine itself, and when I went to look for a title page, I was abruptly met with the first page of a short play, and consequently turned to the internet to provide me with the title of the book as a whole. I also noticed that there was no publication or printer information within the book itself either. What kind of book, even a book of plays, wouldn’t have this kind of information? Isn’t that what makes a publication? Also, when I began to examine the paper from each play, I noticed that each one had a different type of paper: some laid paper with horizontal chain lines while others woven paper with outer-edge watermarks. Even the text font wasn’t uniform between plays, although size looked pretty consistent. For the purpose of this assignment, I chose one of the farces in this book to work with. This play is titled “The Cherokee: An Opera.” While I didn’t have to read it for this assignment, given the year it was written, its title, and its farcical genre, I’m not too disappointed about that.

For the purpose of this assignment, I chose one of the farces in this book to work with. This play is titled “The Cherokee: An Opera.” While I didn’t have to read it for this assignment, given the year it was written, its title, and its farcical genre, I’m not too disappointed about that.