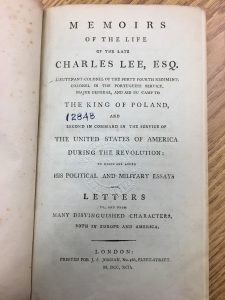

For this assignment I decided return to the book from the first assignment, “Memoirs of the Life of the Late Charles Lee, Esq.,” which was published in 1792.

For this assignment I decided return to the book from the first assignment, “Memoirs of the Life of the Late Charles Lee, Esq.,” which was published in 1792.

I started by opening the book to it’s middle page, thinking I would have the best chance of finding evidence of how it was bound there. But first I noticed that the book was in really good condition and that the pages were trimmed. It seems that this book was stitched together at one point, before being rebound with the sturdier binding it has now.

Looking at the pages, I could see chainlines running vertically, so I knew that the paper was laid and not wove. I also happened to find a watermark on the first page I looked at. The watermarks in Lee’s memoirs show up at the gutter of the upper edge of the leaves, so with one of many references to the Gaskell reading, I figured that I had a decent chance of the book being octavo.

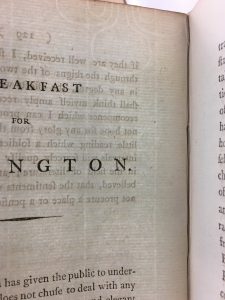

When I started to look at the signatures, I began making notes of everything hoping that what I was looking at would eventually make sense. I also noticed that this book has catchwords. The preface, which was only two pages long, had the signatures b and b2, and the first page of text was marked with a B. The following pages had signatures up to B4, four pages without a signature, and then a page with C for the signature, and this pattern continued throughout the book. This told me that there were 8 leaves per gathering, which made me feel pretty good about having an octavo book in my hands.

When I started to look at the signatures, I began making notes of everything hoping that what I was looking at would eventually make sense. I also noticed that this book has catchwords. The preface, which was only two pages long, had the signatures b and b2, and the first page of text was marked with a B. The following pages had signatures up to B4, four pages without a signature, and then a page with C for the signature, and this pattern continued throughout the book. This told me that there were 8 leaves per gathering, which made me feel pretty good about having an octavo book in my hands.

This book has 452 pages, or 226 leaves, which leads me to believe that it took about 28 sheets of paper to make!