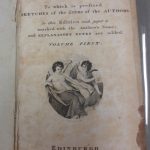

I was pretty close to picking the same book to describe as I did for my first post (since it does, after all, have a few interesting notations at the beginning and end from previous owners), but I ended up selecting another one because I was set on finding one in the original binding. I ended up choosing a book written in 1766 by multiple authors: The Spectator, in eight volumes (see Image 3 in the gallery), which is a series of essays written by Sir Richard Steele, Joseph Addison (Esq.), Eustace Budgell, Mr. Tickell, Mr. Hughes, Dr. Parnell, Alexander Pope (Esq.), Laurence Eusden, Richard Ince, Henry Martyn, John Byrom, Gilbert Budgell, Rev. Richard Parker, Mr. Henley, and Henry Grove. So, basically, a bunch of random names.

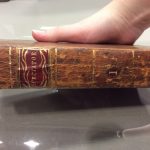

The outside of the book is fairly nondescript save for the spine (see Images 1 and 2 in the gallery). It’s clear where metal tools were taken to the leather; not only are they accented with gold leaf (and red leather dye around the title, as you can see in the gallery) but I could feel the indentations when I ran my finger over them. The actual front and rear of the book feature no distinguishing mark other than redrot (and, to be fair, so does the spine). The endband at the top of the spine has half-broken free of the book, enough so I can see the stitches around it.

With Dakota’s help, because I have problems with processing and conceptualization, we figured out that the book was probably in duodecimo format (12°) by looking at the chart on page 85 of the Gaskell reading. I noticed that the book is printed on laid paper and has very visible horizontal chain lines, and the length of the cut pages is about 17-17.5 cm (roughly 18~cm uncut estimate). The signatures (which go from A-A3 with three blanks, B-B3 with three blanks, etc, all the way until Ee – but skipping J, V, and W) reveal that this particular book has six leaves to a gathering, leading us to the conclusion that the book is likely in duodecimo format. I’m not excellent at math (like, at all), but I think that at 12 leaves/24 pages a sheet of paper, this book probably took 15ish sheets of paper to manufacture.

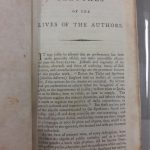

Speaking of the signatures, that’s pretty much the only notable thing there is on the direction line. There are no catch words. However, on the first page of every gathering (A, B, C, D, etc.), there’s a small cross symbol to the right of the signature (see Image 4 in the gallery). I assume this means that all of the pages came from the same press, since the symbol is consistent throughout.

There are only a couple watermarks. On the first blank page I found one reading “1794” (see Image 5 in the gallery – the watermark is faint, but for reference it’s alongside the shadow of my finger). I couldn’t find another watermark on any of the interior pages (probably due to the fact that it’s duodecimo – if I’m right – which means any watermarks probably got cut off) but I did find one on the rear board (see Image 6). If it’s too faint to tell in the picture, it’s a segment of a fleur-de-lis.

There were also a few scribbles here and there, the most notable of which possibly being an owner (see Image 4 in the gallery). I can make out the date as June 25, 1796, and the name seems close to John Whits Smith, but I can’t really distinguish it so your guess is better than mine. There’s also a few pencil marks on a blank page prior to the title page (not pictured because they were too faint in the image) but they indicate that the book was at some point purchased for 3.50 (currency not known).

As for binding, the cover is coming apart slightly, so I could see six places where the paper was sewn to the boards with what appears to be twine, but it’s not much. I couldn’t find anything indicating its state of binding had changed, so I assume I handled it with the same binding in which it had been published.

Finally, cancellations. I have no idea if these count, but I noticed that two pages had been torn out – one right before the title page, and one before the final blank page. They’re right on that teetering point where I’m not sure if they had anything on them to begin with, so I hesitate to call these actual cancellations; I’m guessing someone just needed a piece of paper in a pinch, and decided to utilize some of the blank ones. I did notice that this book had fewer blank pages than some of the other old ones I’ve looked at lately.

If all else fails, I can always blame John Whits Smith-what’s-his-face for those missing pages. I wonder what they were used for.

And then you get to the Special Collections door, shown here.

I (with Dakota) was able to meet with both of the librarians who work behind this strangely fancy door: Gene Hyde and Colin Reeve. They were both lovely, letting us handle the books as well as showing us how to navigate their database – and, of course, welcoming us back anytime (barring the fact that there’s a doorbell outside what I’ve come to call the Marble Gate).

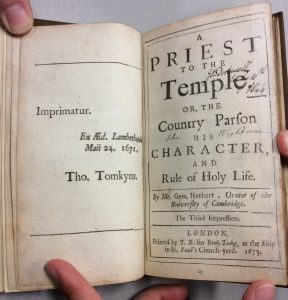

There were a great number of books inside this room (many of them fairly recent, but I’ll touch on that later). There’s room for error, since both Gene and Colin admitted that their database was acting up, but out of this mass of caged books we were able to draw out a strong contender for Oldest Book In Room: A priest to the temple. Or, The country parson his character, and Rule of Holy Life. This book, written by George Herbert and published in 1675, bears clear signs of being passed from hand to hand over the centuries, as indicated by the title page.

This book was rebound on November 26, 1913, as stated by a note scrawled before the title page, but still retains its original pages. It’s just not, you know, falling apart. Before the title page, there are a number of notes with varying degrees of legibility stating who the

And then you get to the Special Collections door, shown here.

I (with Dakota) was able to meet with both of the librarians who work behind this strangely fancy door: Gene Hyde and Colin Reeve. They were both lovely, letting us handle the books as well as showing us how to navigate their database – and, of course, welcoming us back anytime (barring the fact that there’s a doorbell outside what I’ve come to call the Marble Gate).

There were a great number of books inside this room (many of them fairly recent, but I’ll touch on that later). There’s room for error, since both Gene and Colin admitted that their database was acting up, but out of this mass of caged books we were able to draw out a strong contender for Oldest Book In Room: A priest to the temple. Or, The country parson his character, and Rule of Holy Life. This book, written by George Herbert and published in 1675, bears clear signs of being passed from hand to hand over the centuries, as indicated by the title page.

This book was rebound on November 26, 1913, as stated by a note scrawled before the title page, but still retains its original pages. It’s just not, you know, falling apart. Before the title page, there are a number of notes with varying degrees of legibility stating who the  book belonged to, and in some cases under what circumstances.

The earliest entry we found during a cursory inspection was from 1727; it was mostly illegible to me, having been written in script with now-fading ink and all, but we did determine that it belonged to someone named Wells. I think I could pick out a few other random words, such as “Wightman,” “Bosford,” and “Roe.” I don’t know if these are names or places, since they were all written by the same hand and aren’t all formatted the same way. The next dated entry (that we could find) was from July 1, 1878, when this book was given as a “birth day greeting” to a S. Howard Hall. “Soon” after that, the book was rebound as I said by someone with the initials S. H. H. After that, it gets a little fuzzy date-wise. There are pencil marks on the initial pages, seeming to indicate ownership by a library prior to that of UNC Asheville (and relatively recently, at that) and even a price: $220. Gene and Colin mentioned that this book was purchased from a book dealer at some point, but I’m not sure when this happened in relation to said library.

This book kind of doubles as an answer to the first two questions of our assignment (the oldest book and a book that bears evidence of reader use) so I’m going to touch a bit more on this one but briefly throw in another book as a sort of safety net. Clearly, the past owners of this book wanted to stake their claim upon the pages and were not afraid to write in it, but the pages themselves are largely intact. Given that the subject matter isn’t something simple, and also that it covers a largely religious subject in a time where religion was a key part of life (even more so than today in ways), I think it’s safe to say that the owners of this book were purposely very careful to conserve it. Perhaps it held some sort of meaning for them, which might be how it arrived with its pages not crumbling or even dogeared. This stands in stark contrast to another book of which I regrettably didn’t take a picture. Though published later than Herbert’s, this book (something beginning with The pilgrim’s progress, though I didn’t catch the rest) was c

book belonged to, and in some cases under what circumstances.

The earliest entry we found during a cursory inspection was from 1727; it was mostly illegible to me, having been written in script with now-fading ink and all, but we did determine that it belonged to someone named Wells. I think I could pick out a few other random words, such as “Wightman,” “Bosford,” and “Roe.” I don’t know if these are names or places, since they were all written by the same hand and aren’t all formatted the same way. The next dated entry (that we could find) was from July 1, 1878, when this book was given as a “birth day greeting” to a S. Howard Hall. “Soon” after that, the book was rebound as I said by someone with the initials S. H. H. After that, it gets a little fuzzy date-wise. There are pencil marks on the initial pages, seeming to indicate ownership by a library prior to that of UNC Asheville (and relatively recently, at that) and even a price: $220. Gene and Colin mentioned that this book was purchased from a book dealer at some point, but I’m not sure when this happened in relation to said library.

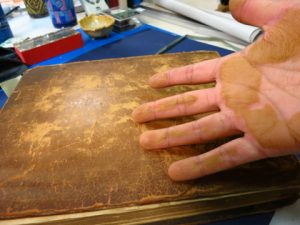

This book kind of doubles as an answer to the first two questions of our assignment (the oldest book and a book that bears evidence of reader use) so I’m going to touch a bit more on this one but briefly throw in another book as a sort of safety net. Clearly, the past owners of this book wanted to stake their claim upon the pages and were not afraid to write in it, but the pages themselves are largely intact. Given that the subject matter isn’t something simple, and also that it covers a largely religious subject in a time where religion was a key part of life (even more so than today in ways), I think it’s safe to say that the owners of this book were purposely very careful to conserve it. Perhaps it held some sort of meaning for them, which might be how it arrived with its pages not crumbling or even dogeared. This stands in stark contrast to another book of which I regrettably didn’t take a picture. Though published later than Herbert’s, this book (something beginning with The pilgrim’s progress, though I didn’t catch the rest) was c rumbling so badly that it had to be kept in an envelope. The original leather binding had a severe case of redrot, to the point where half of it had fallen off entirely, and the pages themselves had separated in the middle of the binding. (The picture here is not of the book in question; it’s just an example of redrot I found. The actual book was in way worse condition.) I know Herbert’s book was rebound so it’s not really a fair comparison, but the pages (which were intact in both books) showed a clear difference nonetheless. I’d hazard a guess that either the owners of Herbert’s book valued it more than the owners of the other book valued theirs, or the latter book just passed through way more hands. Or both.

The most notable collection in that room, though, wasn’t nearly so old. And it’s a cookbook collection, of all things: The Pamela C. Allison Cookbook Collection, spanning from 1932 to 2015. Gene and Colin had a great time describing their adventure to Pamela’s house to retrieve the cookbooks; there were around 3000 of them just piled around this woman’s house. They only took 1000 or so (those that ascribed to the common theme of Southern cooking) but those fill up two large bookshelves in the Special Collections room and are continuing to expand. In a statement available on the UNC Asheville Special Collections website, Pamela herself wrote “My cookbook collection is rooted in three seemingly unrelated interests—good food, reading, and research.” She combined her childhood love of her grandmother’s cooking with her desire to broaden her reading sphere, and started amassing cookbooks until it became an obsession. One of the professors here, Dr. Erica Abrams Locklear, was teaching a class that explored culture through cookbook literature, which motivated Pamela to donate her collection for the good of the Asheville community. She’s still collecting today.

Near the end of our meeting, the discussion turned to the librarians’ most valuable commodities. Though we did discuss the value of a book or two, they made clear that their collection wasn’t based on value. Half-jokingly, they told us that their most valuable commodity was space, and they were running out of it fast. It’s pretty clear just by looking around the room; all of the protective bookshelves were almost entirely full, and the normal bookshelves housing the cookbook collection were almost sagging under the weight of the number of books crammed into it. There’s so much crammed into each book, too; look how long I spent rambling about one or two books in this post, not even delving into content. I hope they can figure out plans for either increased storage or expansion; it won’t be good when we run out of room for this kind of knowledge.

rumbling so badly that it had to be kept in an envelope. The original leather binding had a severe case of redrot, to the point where half of it had fallen off entirely, and the pages themselves had separated in the middle of the binding. (The picture here is not of the book in question; it’s just an example of redrot I found. The actual book was in way worse condition.) I know Herbert’s book was rebound so it’s not really a fair comparison, but the pages (which were intact in both books) showed a clear difference nonetheless. I’d hazard a guess that either the owners of Herbert’s book valued it more than the owners of the other book valued theirs, or the latter book just passed through way more hands. Or both.

The most notable collection in that room, though, wasn’t nearly so old. And it’s a cookbook collection, of all things: The Pamela C. Allison Cookbook Collection, spanning from 1932 to 2015. Gene and Colin had a great time describing their adventure to Pamela’s house to retrieve the cookbooks; there were around 3000 of them just piled around this woman’s house. They only took 1000 or so (those that ascribed to the common theme of Southern cooking) but those fill up two large bookshelves in the Special Collections room and are continuing to expand. In a statement available on the UNC Asheville Special Collections website, Pamela herself wrote “My cookbook collection is rooted in three seemingly unrelated interests—good food, reading, and research.” She combined her childhood love of her grandmother’s cooking with her desire to broaden her reading sphere, and started amassing cookbooks until it became an obsession. One of the professors here, Dr. Erica Abrams Locklear, was teaching a class that explored culture through cookbook literature, which motivated Pamela to donate her collection for the good of the Asheville community. She’s still collecting today.

Near the end of our meeting, the discussion turned to the librarians’ most valuable commodities. Though we did discuss the value of a book or two, they made clear that their collection wasn’t based on value. Half-jokingly, they told us that their most valuable commodity was space, and they were running out of it fast. It’s pretty clear just by looking around the room; all of the protective bookshelves were almost entirely full, and the normal bookshelves housing the cookbook collection were almost sagging under the weight of the number of books crammed into it. There’s so much crammed into each book, too; look how long I spent rambling about one or two books in this post, not even delving into content. I hope they can figure out plans for either increased storage or expansion; it won’t be good when we run out of room for this kind of knowledge.