Habent sua fata libelli.

[Books have their own fate.]

-Maurus

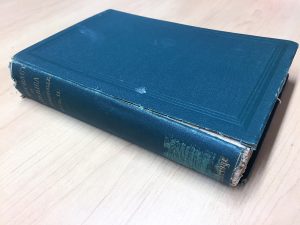

Now that we’ve tackled understanding and recognizing the physical production of books in this course – something that is relatively regulated and widespread – we’ve come to a more personalized, if not rather intimate, study of bibliography. This past week we’ve been tasked with exploring the living history of a single book; it’s life. The book I chose lept at me from my university library’s Special Collections as I was browsing a particular section called the Wadsworth Family Papers: an 1864 copy of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (vol. II).

This book was nestled between land/business documents and books written by particularly well-known members of this extraordinarily influential small-town family. The Wadsworths are mega-stars in Geneseo, NY, where I attend university. This family settled the area around 1790 and maintained considerable control over the majority of Livingston County throughout the 19th century and into the 20th. My college, the State University of New York at Geneseo, owes much of its existence to this family of educated farmers-turned-politicians, and embraces them and their history in the Special Collections of their library.

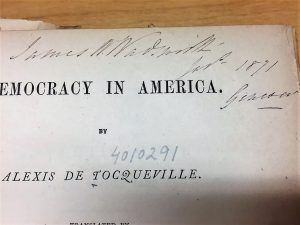

As most of the Wadsworth Family Papers collection is made up of primary sources from the family’s history – that is, business, land, and personal documents, photography, and books written by them – it was somewhat surprising to see an ordinary, widely-read book included on the shelves. As soon as I took it down and opened to the title page, I began to understand why. Note the inscription shown on the two pictures of the title page: “James W. Wadsworth – Jan. 1871, Geneseo.” This was a personal book of James W. Wadsworth himself: an influential farmer, then Civil War soldier, then U.S. Congressman.

Publication Information

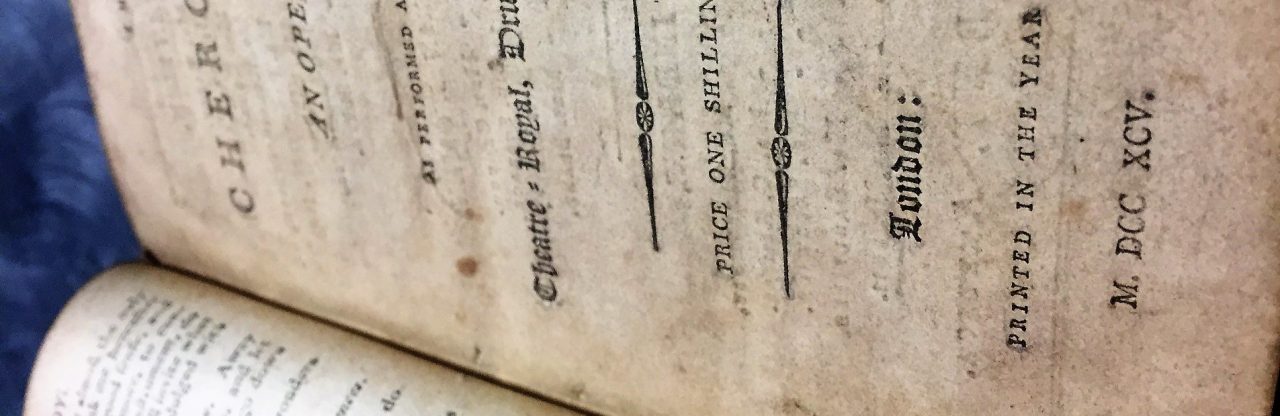

This copy of de Tocqueville’s book was published in Cambridge, MA in 1864 by an American publishing company called Sever and Francis. Democracy in America was written by Alexis de Tocqueville, published in 1838 as analysis of early 19th century America and its flourishing democratic system. De Tocqueville’s motivation behind this study was to look at American democracy as a model for his own country of France following their revolution. It is still today considered one of the most important references for discussing both the American nation and the democratic system. So, the intended audience, at the time of its creation, was perhaps the French nation as a model, perhaps the American nation as a mirror, perhaps both; but most certainly the people who are interested in learning about the way in which achieving equality necessitates a change in social status for many.

Owner Information

As mentioned, this book was originally owned by James W. Wadsworth, and ultimately given to Milne Library at the State University of New York at Geneseo in 1976 by Mrs. Reverdy Wadsworth after the death of her husband, James’s great-grandson. Once the book was given to Milne Library, it was ultimately placed in the Wadsworth

Family Papers collection, effectively kept out of circulation. There is some speculation as to whether or not it had been accidentally put into circulation when it first arrived, but even if it was, it would very quickly have been taken out given its condition.

Marginalia

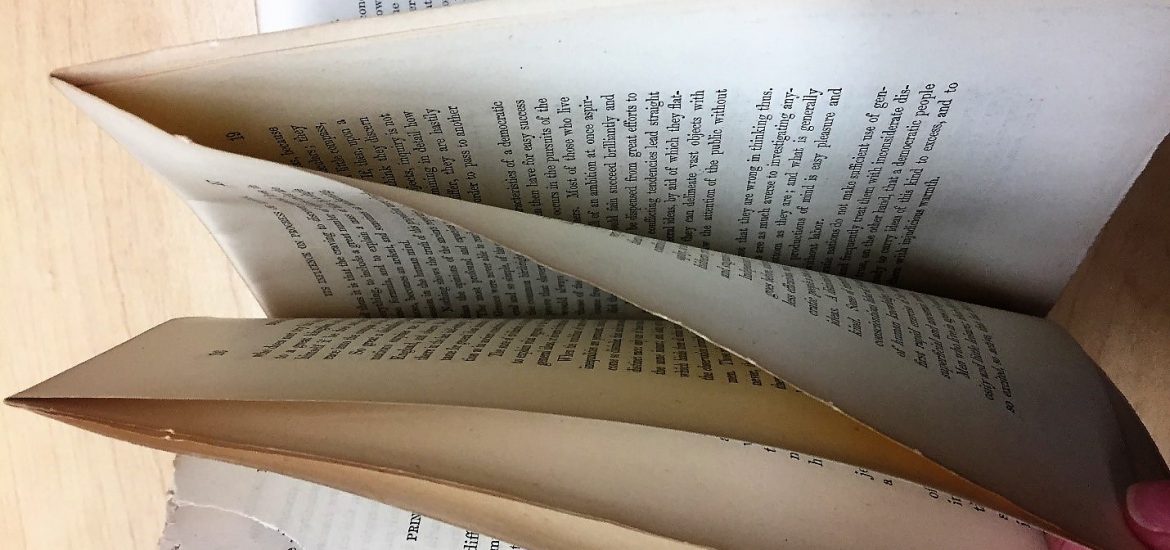

How can I say so confidently that James W. Wadsworth was the original owner, even though there is a span of 7 years between its publication and his mark of ownership? Well, this book is in what I consider to be, with regard to my very little experience with bibliography, very interesting condition; or, at least very telling condition. As shown in Fig. 4, there are multiple occurrences of uncut signatures in this book.

In fact, as not shown in this picture, most of the book is made up of uncut signatures. As you can see in this and Fig. 5, the areas that are uncut are very roughly and crudely done so. While it might seem that this could be indicative of a neglected book, as shown in Fig. 6, the areas of the book that are cut free from their signatures are heavily underlined and even starred.

These markings are done in pencil, unlike the inscription made at the beginning in ink. In my opinion, the use of pencil implies a studious nature of reading, and the thoroughly marked areas of interest imply a purposeful reading, perhaps by someone who understood the book enough to cut the signatures in the correct place to find the information he wanted to highlight. Perhaps this wasn’t the reader’s first time reading a copy of de Tocqueville.

Current Home

Now resting in Milne Library’s Wadsworth Family Papers collection, this book’s purpose and use has unavoidably shifted. Considering it is no longer in circulation and has spent the past 41 years in a locked room for preservation purposes, I’d say that its use has indeed changed since it was owned by James Wadsworth in 1871. No longer is it turned to when de Tocqueville’s words of wisdom are needed; in fact, his voice is but a tiny echo almost completely consumed by the legacy of James W. Wadsworth to which this book is now irrevocably tied. Instead of reading it for de Tocqueville alone, it’s read for Wadsworth, and represents Wadsworth now far more than de Tocqueville.

Follow the dynamic Timeline JS I’ve created for this post to see the history of this book come to life!